Bioshock Infinite: Part One, Part Two, Part Four

WARNING: Some mild spoilers for Bioshock Infinite.

This post is going run along the general theme of “they could have done better.”

I can only speak for myself, but I was expecting racism to be a more significant theme in Bioshock Infinite based on information that we were told about the game. That expectation likely altered my opinion of the way Irrational handled race relations in the game in a way that it wouldn’t have been altered if I’d just gone into the game without any knowledge. But I still believe I would have noticed the things I’m about to talk about, so I think it’s a valuable topic for discussion.

I wouldn’t say that I was outright upset by the handling of racism in the game, but I do think that Irrational flubbed the theme. Racism became an easy way to paint Comstock as a villain and show that Columbia wasn’t such a utopia rather than a topic that was handled as important in itself. I found racism in general to be a much less intriguing topic than a lot of the other strange and fantastic ideas that Bioshock Infinite put forth, solely because of the trite and simple way the game handled race. In such a thoroughly well-crafted game, this is a real shame.

The way Bioshock Infinite handles race, is similar to the way I learned about racial prejudice in an American elementary school. Being racist is bad. Now let’s watch a movie about the Civil Rights Movement with a completely evil white racist Southerner as the villain. (All racists are very easy to spot, you see.) Racism ended in the 60s, kids! We won’t be talking about modern day racism. In fact, when learning about the Civil War, we won’t be mentioning Northern racism. The South were the bad guys, because they liked slavery. Slavery and the suppression of voting rights are the only way racism manifests itself.

I wouldn’t call any of what I was taught malicious — far from it — but it was an incomplete picture of what racism was and is like in the United States. And it’s easier to show a kid something obvious like slavery in order to get across the message “racial prejudice is bad” than teaching them anything more nuanced — especially when those nuances are tied up in the constant scuffling of the American political party system.

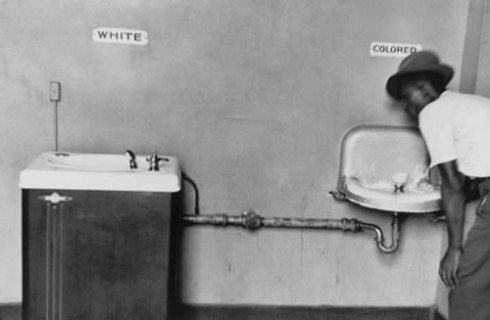

Bioshock Infinite tends to go for the easy when it comes to race. Black people are shipped up to Columbia as workers, who are essentially slaves and second-class citizens to their wealthier, white counterparts. In case the parallels to the history of American racism aren’t obvious enough, Irrational is kind enough to include race-segregated bathrooms in the game. I doubt there’s an American school child who makes it through their education without seeing at least one image of a racially segregated water fountain: an easy to understand image that makes the racial hatred of black bodies starkly apparent.

There’s nothing particularly wrong with being a bit obvious in setting up a theme of racism. And I can accept that Columbia is an openly racist, white supremacist society. I think the problems start to occur when hours of gameplay and story go by without any added nuance to what is a major element of the world-building of Columbia.

The problem with the two-dimensional white racist in all those movies about the American Civil Rights Movement isn’t that those people didn’t and don’t exist. It’s that the majority of people are not like that. Many people held (and hold) racist beliefs that were normative at the time but were harmful in that they helped keep the racist status quo.

I found there to be little of this nuance in the people of Columbia. They were all just… terrible. Fink was abhorrent, the random racist comments of the NPCs were said in the most obnoxiously snooty way possible, and the only minor NPCs who help you are members of the anti-racism league.

I understood where Irrational was going with the rebellion of the Vox Populi. Something like “power corrupts no matter what,” which fits well with the themes of the game. But I found myself having trouble raising my ire about the Vox Populi’s violent uprising when their anger seemed warranted. If a single white Columbian had ever once been kind to them, I would have been surprised. And they were so physically separated and segregated in Shantytown that it was unlikely the Vox had any real connections or relationships with white Columbians at all. Why should they care? And why should I care about the chaos and murder that takes over Columbia?

- I won’t say white savior, but…

Because that was a real missed opportunity. In the grips of the personal story between Booker, Elizabeth, and Comstock, the wider picture gets lost. I would have liked to feel some sadness or guilt at the downfall of Columbia. As it was, it was a city of racist cult members, and the world seemed not only better off, but safer, without them.

My guess is that the loss of the racism thread in the overall tangle of the plot was a result of changes in development. What started out as a story about a place (much like the first Bioshock) turned into a more personal story. And so what seems to be an important plot element in the beginning of the game — racism — becomes mere backdrop by the end, and barely even that.

As a serious social injustice that still affects millions worldwide, racism is used as an easy brush with which to paint the villains of Bioshock Infinite as bad. In a game that has generally good writing, it’s disappointing to see the writers go with what amounts to cheap and easy emotional manipulation. I would have preferred a more morally ambiguous Columbia full of inhabitants with differing opinions. I do believe, however, that this was sacrificed in the name of the central conflict between Booker and Elizabeth, which has its own merits.

I also think that this game does poorly for modern racism, which is certainly not only a problem with this game. The racism in Bioshock Infinite is couched securely in American history. Columbia is distilled old-timey, American imagery based on a fake nostalgia for an America that never existed but is still held dear by Comstock and his followers.

Sadly, I don’t think a lot of Americans have the best grasp on American history to realize that America was never all apple pie and kids riding their bikes outside until dinner time. Especially, you know, if were a black American.

I would say that Bioshock Infinite plays with this false nostalgia (which is certainly present in American politics today), but never pushes it very far. The game, like all of those overcoming-racism movies, subtly encourages the narrative that true racism exists in America’s past. We’re over the worst of it now, and the only really bad racism that exists now lies in those few people who go to KKK meetings.

After all, it would be easy to think, “Columbia sure is racist. And, man, America sure was racist too. But that’s not what my society looks like now, so we’re not racist.”

If only that were true. Racism is a much quieter force than what is portrayed in Bioshock Infinite, and it’s all the more pernicious for it’s quietness. The racism of the past might seem obvious to us now, but it wasn’t always so obvious to those who existed at the time. And you can be sure that the racism of today will be much more obvious to our descendants.

Bioshock Infinite isn’t trying to be a treatise on modern racism, and I’m not trying to claim that it should be. The game does a great job of evoking exactly what this imagined “ideal” America would probably look like in real life, especially for those who wouldn’t win the white, wealthy lottery. But the game eventually drops the complexity and uses racism more as set dressing and as a cheap way to characterize villainy, and I believe the game should be interrogated closely for that.

It might seem like I just want the game to be more about racism, but that wouldn’t really fix the problems of poor implementation. The world of the game is informed heavily by Columbian white exceptionalism, making race a large factor already. My problem is twofold and related: the racism in the game draws upon imagery of American racism without the content of real, historical racism (I’ve seen far too many people say things along the theme of, “So this is what racism was like!”) and this unrealistic treatment of racism — while it technically works for the plot — flattens the world and people who live in it. The overly simplified version of racism in Columbia basically turns into a writing shortcut to make the player understand that Columbia = bad. A bad Columbia is kind of boring, especially when the ruination of a more complex Columbia would have played so well into Booker’s massive guilt trip. It smacks so sadly of a lost opportunity. Once again, my mantra of “games need to be written well and thoughtfully!” returns.

So how can we move toward better writing, especially when dealing with social realities like racism? In my ideal future developers would ask themselves a few questions while working on their games: Why am I including this topic? Am I handling it responsibly? Is it essential to the plot, or can a similar idea be conveyed in a less conventional or more intriguing way?

What it comes down to once again is responsible, well-thought out, and complex writing in games. I’m confident we’ll get there eventually, and I do actually count Bioshock Infinite among the games that are getting us there. One topic handled poorly does not a bad game make.

What do you think? Was racism actually handled really well in Bioshock Infinite? What perspectives am I not considering?

Hi! (It’s Jill!) I haven’t played this game yet but I’m itching to try it out. I read your post because I don’t really care about spoilers that much and because it was really interesting–these are such good points, and people who have played the game seem to agree with you. It’s interesting that Columbia is floating; it reminds me of the city of Laputa in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, which flies around and basically bullies the people below into doing whatever it wants them to do. A lot of people seem to agree that Swift was using this as a metaphor for colonialism and/or racism, but what is interesting is that Swift was not very decisive on the issue; he hated the Catholic Irish (who were the “people below” in the floating city metaphor, as opposed to Swift’s own Protestant, landowning minority) and probably agreed with popular conceptions of African/Caribbean slaves at the time, but he realized that there was something wrong with these attitudes. It’s funny that the racism in this game was presented as “easy,” as you say, when I see a definite resemblance to Swift’s text!

And also, I want to clarify, from all I’ve heard and seen, I agree with you! 🙂

And the Catholic Irish weren’t actually the people below in the metaphor (sorry), but his point was that those below, even if they were Protestant, were realizing what it felt to suffer under oppression, like Catholics (and slaves, if we’re looking at the larger picture) did, due to an unfair monetary policy placed on Ireland by England (above) at the time…Swift, being Anglo-Irish, was in a bit of a scary position because even though he was technically part of the Irish ruling class, he was sometimes thought of as part of a “native” or “savage” race for being Irish at all, and often linked to the Catholic Irish (who were themselves compared to “native” peoples who were supposedly inferior to English and/or white people)…

I will stop harassing you in the comments now. XD Great post on The Last of Us, too! (I just finished it and now I have to go find the work I threw into a corner because the cordyceps apocalypse was happening, goshdarnit, and I couldn’t deal with work at a time like that.)

Thanks for the comments, Jill! You should play the game soon — I’d be interested in hearing what you think after you’re done. Now that you’ve brought it up, I can see some definite connections to Laputa. I would have loved to see the game explore the dynamic between Columbia and the land below. Maybe some of the different dynamics of oppression there would have made me feel better about the messages about race in the game.

I think the racism aspect may have been better if one of the main characters was non-white. As it is, there is no danger to Booker and Elizabeth besides fleeing Comstock.

I agree, and I also think the story would have be told differently.

As it is, we have the stunning hypocrisy of Booker and Elizabeth tearing through the city to release Elizabeth from imprisonment, murdering everyone in their way, while they condemn the Vox’s uprising and Daisy as being just like Comstock. The writers seem talented enough to have realized the parallels between Elizabeth and the Vox’s situation (trapped on Columbia against their will, treated as subhuman — although the Vox have it worse than Elizabeth), and maybe they tried to use the condemnation of the Vox’s revolution to add another layer of critique to Booker’s actions. But Booker gets the full character development treatment and is ultimately redeemed in the end through baptism while the Vox wind up as fancy setting/plot dressing more than anything else. It was definitely, at the very least, distasteful to me to have these two white characters criticizing the Vox for a situation that Booker and Elizabeth would never find themselves in.

Sorry for digging up an old piece, but I just finished the game and am processing. I agree with everything you’ve said, but just want to add that I think the “moral” (sorta) of the story in the end is relevant. It’s revealed that the decisive difference between Booker and Comstock is their choice to be baptized or not. This means that the racist / xenophobic / american-exceptionalist city of Colombia is literally founded on the mindset of being able to be absolved of one’s past and reborn—hence baptism being necessary to gain entrance. Especially because Booker’s sins are so steeped in racism and so rooted in the genocidal past of this country, it seems like the message is that we (modern US) have to dig up the sins of our past and face them rather than trying to forget them.

I’m not sure how this squares with the ending though, since, Booker’s attitude is not a perfect alternative to Comstock’s… And yea, I really wish they had handled the Daisy / Vox plot better.

Thanks for the article though! Your blog is really cool!